At the close of the 19th Century, the Indian wars shifted from the battlefields to the courtrooms. Most often the courts were used to separate Indians from their land. The Dawes Act of 1882 was designed for just such a purpose and to force Indians to assimilate into mainstream American society. Indian Boarding Schools modeled after the famed Carlisle Indian Boarding School were opened across the West with the purpose of assimilating a generation of Indian children. The ultimate goal of assimilation was to open the reservations to white settlement and to terminate treaty obligations.

In 1892 the small Indian Pueblo of Isleta, 10 miles south of Albuquerque, threatened a lawsuit against the Albuquerque Indian Boarding School. The school was holding 15 Pueblo children against the wishes of their parents. In standing up for their children the Pueblo was also taking a stand on cultural preservation, Civil Rights, citizenship and Native sovereignty.

By the 1880’s, the Indian Pueblo of Isleta had been in existence for over 450 years. The previous 250 years were under European influence, first Spanish and then Mexican. The Pueblo’s religious practices were a blend of both Catholic and Native beliefs. The Catholic Church and Mission school had been an integral part of the community since the 1700’s. In 1882 the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad established a refueling station at the Pueblo. The Railroad brought increased American influence and threw the Pueblo into a social and political upheaval. Some members of the Pueblo believed that they should actively oppose American cultural influences. Others felt that they key to their survival was to adapt to the new culture.

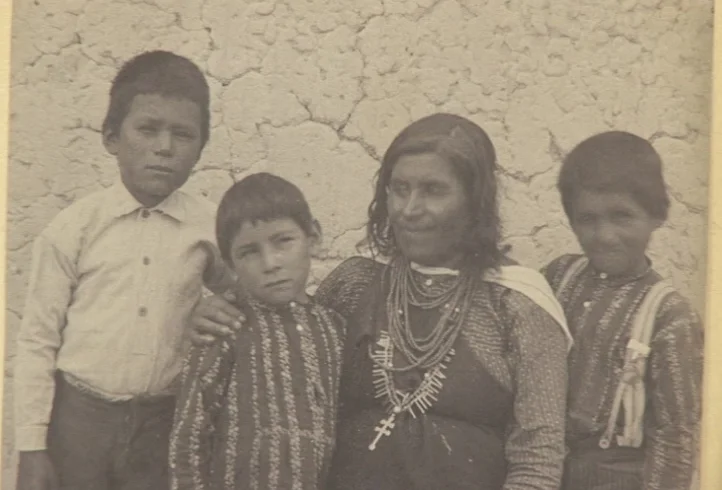

Juan Rey Abeita and his wife Pita believed it was in the best interest of the Pueblo to adapt to the new cultural and sent their two older boys to the Albuquerque Indian Boarding School to prepare them. They also took the unprecedented step of renting a room in their adobe compound to an outside, a white man.

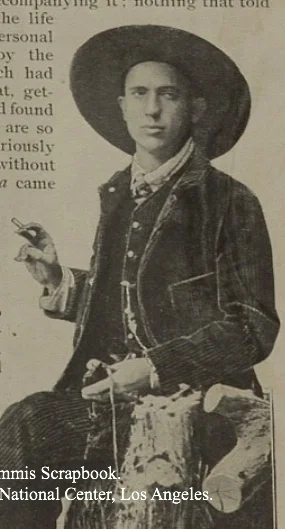

Charles Fletcher Lummis established his national reputation as a writer in 1884 when he walked from Ohio to Los Angeles as a newspaper stunt. In the Spring of 1888 he suffered a stroke that paralyzed his left side, ending his career as the first City Editor of the fledgling Los Angeles Times. He moved to New Mexico Territory to recuperate and began a career as a freelance writer. He supplied the territorial newspapers with articles on business and politics while he supplied the Eastern magazines Western stories that featured his Mexican and Native neighbors.

As headmaster of the Albuquerque Indian School, Creager believed that any contact with tribe or family caused the children to backslide into tribal culture. Creager decreed that all contact between children and tribe or family should be cut until the child graduated at age 18. He banned all trips home and curtailed visitation rights of parents. This was a source of great distress to the families of Isleta and they spoke of their missing children as “Los Cautivos” the Captives.

The Indian Rights Association was founded in 1882 and was a highly influential reform movement that was struggling with the “Indian Question.” Roughly put, the question was one of annihilation versus assimilation. Many Americans felt that Indians could never adapt to American society and must be eradicated. The Indian Rights reformers believed Indians could be assimilated through education. They favored the Carlisle Boarding School model of education that sought to re-educate Indian children by changing their names, their religion and their language. This was a cultural genocide, rather than a physical genocide. This reform movement, reflecting the attitudes of the times, was only open to Protestants and was virulently anti-Catholic.

When Benjamin Harrison was elected President in 1888, he appointed a number of IRA reformers to the Indian service. Thomas Jefferson Morgan was Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Daniel Dorchester was Superintendent of Indian Education and William Creager was appointed headmaster of the Albuquerque Indian Boarding School. None of these men had any prior experience with Indians.

As headmaster of the Albuquerque Indian School, Creager believed that any contact with tribe or family caused the children to backslide into tribal culture. One of his initial acts was to change school policy. He decreed that all contact between children and family or tribe should be cut until the child graduated at age 18. This was counter to the rules under the previous headmaster, who favored a liberal vacation and visitation policy. This new policy was a source of great distress to Pueblo families and they called their missing children “Los Cautivos” or “The Captives.”

In response to the ban, Pueblo families across the Southwest stopped sending their children to the government run school. As Federal funding for the school was tied to enrollment, Creager began kidnapping children to ensure a full budget. Three-year-old Tuyo Abeita was one of the children abducted and taken to the Albuquerque school. Creager relied on the legal argument that since Indians were considered “wards of the State,” the government could ignore claims of sovereignty or citizenship, and do what it deemed best for the Indians.

For most Americans, Indians were at best, an abstraction. For Lummis, they were his friends and neighbors. He experienced first hand the suffering of the Abeitas. As Lummis developed stories about Indians for the Eastern magazines, he wrote about their culture, their traditions and their interactions. His human depiction of the Indians contradicted the prevailing prejudices of the time and his stories attracted a large audience. His stories often contradicted the policies of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and frequently challenged them.

When Commissioner Morgan toured the region, the Pueblo of Isleta asked Lummis to intervene on their behalf to see if they could get their children released. The meeting did not go well. Morgan told Lummis that the Indians had no rights to allow “their children to grow up like themselves – a race of barbarians and semi-savages.” In his diary, Lummis referred to Commissioner Morgan as a “tenderfoot.”

In the article “Poor Pedro: The Plight of the Indian Who was Educated” Lummis told an allegorical story of Henry Kendall, nee Domingo Jiron, an Isletan boy who graduated Carlisle Indian School. Henry returned to Isleta fired with a missionary zeal to convert his tribesmen from “superstitious Indians” into good Americans. The Pueblo resisted his efforts and shunned him. The Anglo society he sought to join proved to be too bigoted to accept him, leaving him an outcast of both cultures.

Lummis’s articles had a positive affect on public opinion and people began questioning government education policy. That Lummis got under the skin of the Washington bureaucrats became evident in the yearly report of 1892 by Superintendent of Indian Schools. In it, Daniel Dorchester referred to Lummis as an unnamed “magazine writer” that opposed reform.

After nearly three years without their children, the Pueblo Council asked Juan Rey Abeita to travel to Albuquerque and make a direct request. Upon arrival, Juan Rey was denied entry, by school guards, told he would never see his children and then they beat him.

The Pueblo Council called a meeting and asked Lummis to attend. After examining the situation they asked Lummis for his opinion. He suggested filing a lawsuit. The Council agreed. Using his own money, Lummis hired a Catholic lawyer to sue the Protestant reformers. Joseph Marron filed a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of Juan Rey’s three boys.

Confronted with the possibility of a precedent setting legal decision with national implications, Dorchester instructed Creager to settle out of court. The night before the case was to go before the Judge, Creager sent school guards to Isleta to intimidate Abeita. He didn’t count on the pugnacious Lummis who stood down Creager’s tough guys. The morning of the court date, while Lummis and Abeita were preparing their case with their attorney, a messenger arrived from Creager. He was ready to settle. Lummis and Abeita secured the release of 15 children that day.

In newspaper articles Lummis recounted the emotional homecoming as the rented wagons loaded with children entered the Pueblo Plaza. Especially poignant was the reunion of Pita Abeita and Luis. For mother couldn't talk to her son as Luis had lost his language and could speak only English. Eva, Lummis’s wife, had to act as translator. “And Pita --- as fine and motherly a woman as I ever knew---cried; and Luis cried; and so I think did we all,” wrote Lummis.

Later that year Congress passed a bill that required that boarding schools could only take Indian children with the permission of their parents. By 1893 the Senate forced Morgan to resign. Morgan’s replacement, D.M. Browning admitted, “Even superstitious and backwards people have a right to their children.”

Although this was a positive outcome for the Pueblo, had Lummis persisted with the lawsuit, perhaps it would have had a national effect for all Indians. As it was, the government quickly learned how to coerce parents into signing away their children, either by threats and intimidation or by withholding necessary annuities. The Indian Boarding School remained active for another 100 years, finally closing at the beginning of this century.